Who was the last Englishman to stand up to the French?

Which annual religious festival held in Ely leant its name to a word meaning “showy but cheap and of poor quality”?

Who were the Littleport rioters and what did they do that was so bad that five of them were executed?

I subscribe to the theory “that the past is a foreign country”. I’m not that old, but when I was young I lived through times that we now look back on as being of great change. However to me at the time change was invisible – its was ‘same old – same old’. The Prime Minister was always either Ted Heath or Harold Wilson, and I was too young to realise that the 1960s were ‘swinging’. We all know that Fenland used to be very different. A marshy and difficult land with no proper roads and only a few tracks that were impassible in Winter. Often the only way to get around was on stilts or by water. In winter there were dehabiliting freeze-ups. The Fen Ague was a malaria like illness which did for local boy ‘made good’ – Oliver Cromwell. After the great freezes, came great floods. The struggle for existence was the battle against the elements.

In our modern sanitised society with proper roads and successful water management, the past can appear to have disappeared. But scratch the surface – and its echoes are often still to be heard !

One of the best means of rediscovering that past is through literature. There are three books which I particularly treasure and which vividly evoke a Fenland past.

These are Hereward the Wake: Last of the English. This was published in 1866 by the Rev Charles Kingsley (also known for writing the Water Babies). It tells of events in 1071/2 when the Anglo Saxon leader Hereward led resistance against the conquering Normans (1066 and all that) from his base in Ely. It popularised Hereward and elevated him into a Robin Hood type hero. There are varying accounts of Hereward’s life and struggles. I recently read one by an eminent historian denigrating Charles Kingsley’s as being hugely inaccurate. Somewhat in disgust I put aside this anaesthetised version and returned to Kingsley’s rip-roaring, dramatic and exciting version of this gripping tale!

Aldreth GOBA Mooring Fens Sunset

It is difficult to imagine both life, and the pre-drainage landscape nearly 1,000 years ago. But Kingsley brilliantly paints a picture. Hereward refused to swear allegiance to the invading King William (a.k.a. ‘William the bastard!). He brilliantly defeated William’s troops at the river crossing on the Old West River near Aldreth as they marched on Ely from Cambridge. There is a remote GOBA mooring near this spot and a farm bridge now crosses the river. We’ve enjoyed mooring here several times, and I can report that we haven’t (yet) been troubled by the ghosts of the long slain Normans.

Aldreth Bridge River Ouse

Hereward was later betrayed to William by the monks of Ely. There is a strong suggestion that Hereward’s successes relied heavily on the support and advice of his first wife Torfrida. However he was persuaded to divorce her and instead marry Alftruda, who in modern terms could be described as ‘more celebrity’. Under her influence he wimped out and lost his fire, eventually submitting and swearing allegiance to William the Conqueror.

Hereward

Walking down Ely High Street I recently noticed a pupil of King’s School Ely wearing a sweat shirt emblazoned “Torfrida”. On inquiry I learned that one of the school’s houses is called Torfrida. I was delighted to learn that the ‘real brains behind Hereward’ had been so commemorated. (one of the other school houses is called Etheldreda – another name with major resonance in Ely !)

Another historical novel which vividly conjures up ‘lost Fenland’ is Cheap Jack Zita, published in 1893 by Sabine Baring-Gould. The period after major wars is often one of great social change. Returning soldiers often cause unemployment, grain shortages and inflation. This was evidenced more recently by the great changes which swept Britain after WWll (leading to the surprise election of a reforming Labour Government and the establishment of the National Health Service). This novel is a wholly fictional account based on actual events. It starts outside the great Galilee porch on Ely Cathedral. The death in 879 of Ethelreda, founder of Ely Cathedral was commemorated annually by holding a fair, St Etheldreda’s Fair, which became commonly known as St Audrey’s Fair. Cheap and flashy goods were often sold at the fair, leading to ‘St Audrey’ becoming abbreviated to the word ‘tawdry’. A ‘cheap jack’ was a seller of cheap inferior goods, typically a hawker at a fair or market. Zita was the eponymous daughter of a cheap jack. This is another fast moving and exciting tale which details the landscape and hardships of the area (particularly along the River Lark). It culminates in May 1816 with an account of the actual the march from Littleport to Ely of angry and frustrated rioters. The riot was halted by soldiers and during the following assizes in Ely 23 men and one women were condemned, and five hanged. Plaques commemorate their terrible fate. In Ely, near the Cathedral, and a stone plaque was installed on the west side of St Mary’s Church which ends “May their awful Fate be a warning to others” The other convicts were transported to Australia.

Cannon at the Gallillee Porch Ely Cathedral

The expression ‘the queens of crime’ refers not to female villains, but to the four authors Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh. Dorothy L Sayers (June 1893 – December 1957) grew up in first in Bluntisham, and later in Christchurch where her father was rector. The family seat of her aristocratic fictional detective, Lord Peter Wimsey’s was Denver. Wimsey helped defend his brother, the 16th Duke of Denver, when he became the chief murder suspect in Sayers’ novel ‘Clouds of Witnesses’ in which he was tried by his peers, before the full House of Lords. Her choice of the name ‘Denver’ for the fictional Dukedom reveals her Fenland roots.

Bluntisham church near st ives fens waterways

Her 1934 mystery the award winning ‘The Nine Tailors’ is set in the fictional fenland village of Fenchurch St. Paul. The end of the book includes a vivid description of a massive flood, and it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Sayers must herself have witnessed similar flooding while growing up in the fens. It is rumoured that several characters in the book share names with graves in Bluntisham churchyard.

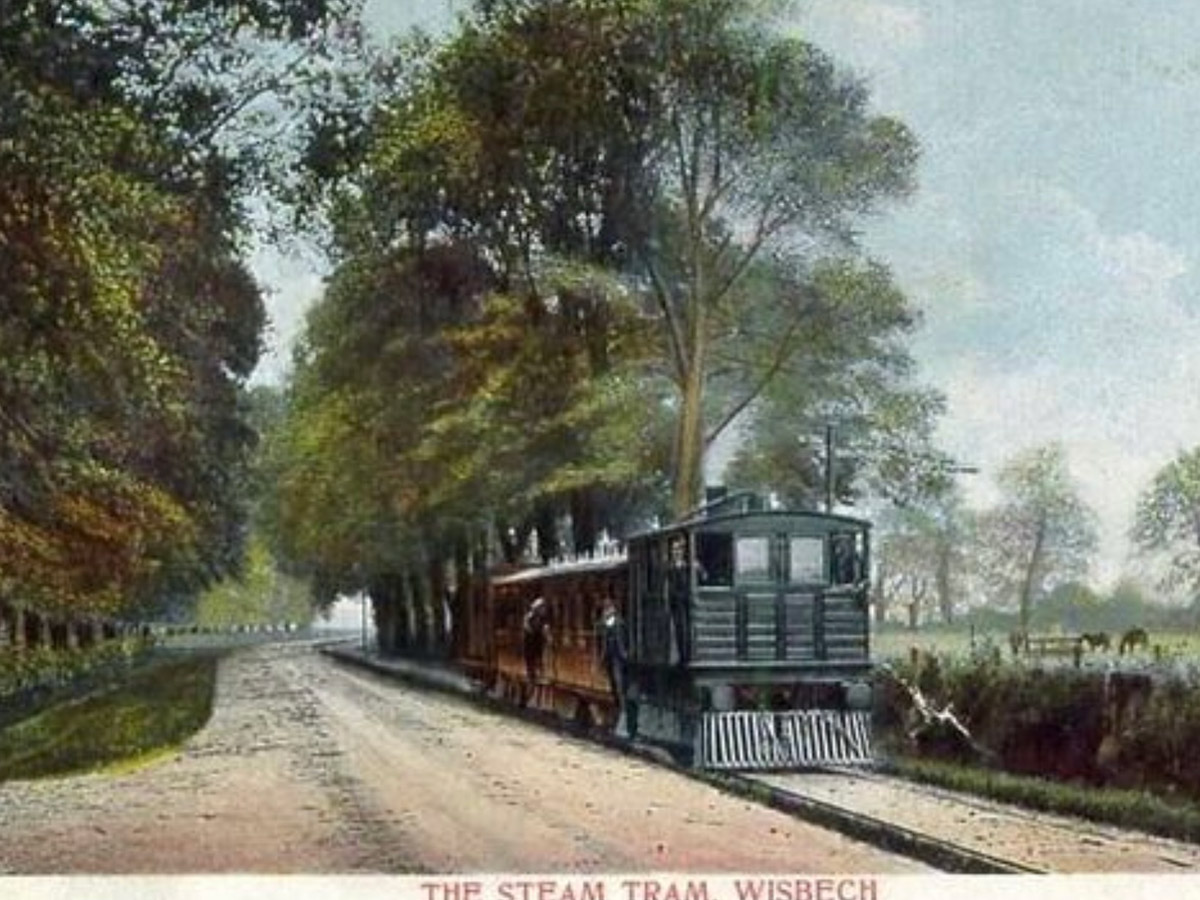

Wisbech Upwell Tramway historic photo

Deserving an honourable mention in our Fenland Literature ‘hall of fame’ is the Rev. Wilbert Awdry (June 1911 – March 1997) creator of Thomas the Tank Engine. The Rev Awdry served as Minister in the South Cambridgeshire villages of Elsworth with Knapwell, Bourn and in Emneth (Norfolk). He was a fan of Wisbech and Upwell tramway, and in his book Toby the Tram Engine, Toby, and the coach Henrietta are based on stock used on the line.

the steam tram wisbech old photo

The last book which, through its powerful and sometimes almost poetic prose, draws us back into a more recent past is Tom’s Midnight Garden (first published 1958) by Philippa Pearce. This story for children slips between a present in the 1950s and a late Victorian past in the 1880s – 1890s. It memorably includes a description of skating from Ely to Great Shelford (near Cambridge) along the frozen rivers Ouse and Cam during the ‘mini ice age’ which permitted the great frost fairs held on the river Thames, and described by Dickens.

Tom’s Midnight Garden book cover

The late Mike Rowse, several times Mayor of Ely, and dedicated local historian, once related to me that Philippa Pearce (the author) once visited Ely Cathedral and read the skating passage from the pulpit. He described it as a moving and unforgettable experience.

I have been a devotee of skating since reading the book as a child. Outdoor skating is an unique experience and it is of great regret to me that warmer winters appear to have largely relegated it to the past!

Cheap Jack Zita, published in 1893 by Sabine Baring-Gould, Tom’s Midnight Garden, written by Philips Pearce in 1958

Blog by C Howes